I read an article recently discussing scope creep. It starts by stating “Scope creep is awful.” Many of the points suggested are good and the recommendations valid, yet at some point I have to ask: Is scope creep really awful?

I was both the client and vendor, for lack of better words, on a home improvement project recently. I learned some valuable lessons related to scope creep over the course of this project, that I believe translate well to the world of digital projects. For anyone reading this that doesn’t know, Chromatic is an entirely distributed team. We have never had an office or a collocated meeting place. Most of the team works from their home, a coffee shop or wherever they happen to be that day; cabins, lakes, and mountains included! I live in a condo located in downtown Chicago and ever since we moved in, I have used a 5ft by 9ft walk-in closet as my office. In early 2017 I decided that I wanted to make a few “small” upgrades to make my closet-office feel less like a closet and more like an office.

Through this experience, I’ve learned that the ways we talk about scope creep, engage our partners/clients, and approach our projects don’t account well for unexpected changes to scope. There are many reasons for this, some of which are out of the control of the people materially involved in the project, but I believe that we can improve this from both sides. Read on to read about the four key lessons I learned.

A small office upgrade project

Here is what my office looked like at the beginning of this project:

I had a simple, defined scope to upgrade a few aspects of my office:

- Remove the carpet and replace it with hardwood floor.

- Build a bookshelf into the wall behind my desk to gain a small amount of additional space and depth in the room.

- Put a new coat of paint on the walls and hang some beautiful artwork.

With the scope of the project clearly outlined, I could easily set a budget and timeline. But here I already hit the first bump in the road. The project wasn’t approved by all of the stakeholders (lesson 1). That’s right, I had the plans in place before getting final approval from the other stakeholder, my wife, Chel. Now to be fair, she knew this was coming and we agreed on the concept before I started, but I was ready to move forward much quicker than she was. This in and of itself, didn’t add to the scope of my project, but it easily could have changed requirements, thus including all of your stakeholders upfront is very important.

I had the scope, the budget ($1,200) and the timeline was: as quickly as reasonable.

The production team was small (just me) so the kick-off meeting went quite well. I determined the first phase of the project would be removing the half-wall where the bookshelf would be built. The demo is always the fun place to start!

The project was off to a great start, the wall was coming out smoothly until I got to the corner. Wait… what is that? The adjacent wall seems to have unused space behind it. Fourteen inches (14in) to be exact, or roughly thirty-six centimeters (36cm) for those of you who use sane units of measurement. Now the project had reached the first crossroad: I could ignore this, or I could expand the room further and actually gain a few extra square feet of space. This would increase the footprint of the room by roughly twelve percent (12%).

One of the goals of the project was to make this room feel bigger, hence the bookshelf being built into the wall. How could I not reclaim this space? Of note, this was an interior wall, I did not take the space from my neighbor, plus there was already another drywalled wall inside the wall.

I did not have a plan to write this post before I started the process or my photos would have been a bit better, but you can somewhat see the space in the wall in here:

Now, the scope of the project was going to change. Being a key stakeholder, the project manager and the ‘developer’ I clearly knew what this meant. The timeline and/or the budget were going to have to change as well (lesson 2).

In this case, the budget needing to change becomes painfully obvious. Let us assume that I had already purchased all my materials for the hardwood floor, the bookshelf and perhaps even the paint and that my estimates were good, even perfect. I would have bought ~45 sq. feet of flooring for the 9ft x 5ft room and lumber to build a 9ft wide bookshelf. I find it unlikely that Home Depot, Lowes or Menards would give me more flooring and additional lumber for free, simply because my scope increased. Nor would they give me the new materials that weren’t foreseen when I started the project (drywall, electrical wiring, etc.).

This was not a problem because I could increase my budget for the project; the extra space was worth the expense. That space would almost fit my whole desk! Had I already spent my entire budget and known I could not spend any additional dollars, I would have had to pass on expanding the scope at this time. In the agile methodology, I would have had to “put it in the backlog.” One note on using the backlog in this specific case, had I chosen to do that when revisiting this feature, it likely would have been a decent amount of redundant work and cost. This could be compared to technical debt.

This change in scope increased both the timeline and budget, but that was OK because it was going to make the final product even better.

Then as I was cleaning and prepping for the next phase, building the bookshelf and finishing the wall, I was visited by the Good Idea Fairy:

What if you opened up the closet to the whole adjacent room?

Major scope creep alert!

This was more or less saying, let me start an entirely different project. This wasn’t the original plan, but as I thought about it more, I decided that this was worth the investment. I consulted the other stakeholder who agreed that this was the way we should move forward with the project. With this large of a change, I knew I had to redefine the scope (lesson 3).

All of the original upgrades needed to remain in scope with the addition of removing the wall between my closet-office and the loft, the lighting and electrical would need to be updated, more drywall would need to be replaced and, finally, I would have to replace all of the carpeting in the loft with hardwood. And don’t forget the whole thing would need to be repainted. (Plus a lot of small details and finish work.)

At the end of the day, none of this was awful. It was all for the betterment of the project. The end result was exactly what I wanted and clearly brought the most value to me, my office and our home. This would have been awful had we not been able to adjust the timeline or the budget for the project.

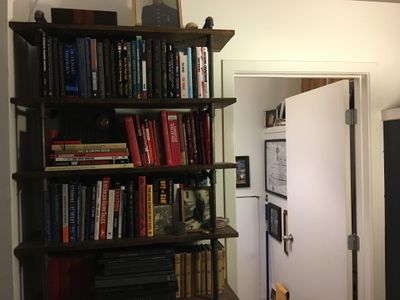

Here are a few photos of the final product:

Scope creep may mean scope improvements

The scope creep of this project made it the best it could have been. And that is exactly why I don’t think scope creep is necessarily awful. The problems with scope creep, changing the scope or redefining a project, come from how we communicate and plan for these changes as well as how we re-adjust expectations with direct and indirect stakeholders.

Specifically, when it comes to creative and technical services, there are unique challenges that need to be overcome. These challenges are both on the provider and the consumer side. Those of us providing services need to account for these changes up front, and frankly, we need to embrace them. Scope creep shouldn’t be a negative phrase, it should be something that we delight in because we know we are building the best products for our partners (lesson 4).

On the consumer side, there is a need to be flexible to changing budgets and timelines. Something I know is easier said than done at times. However, to find the best solutions so that we all win, a level of flexibility is required.

Here’s to scope improvements in 2018!